| <- Back to main page |

|

by Joel Van Valin

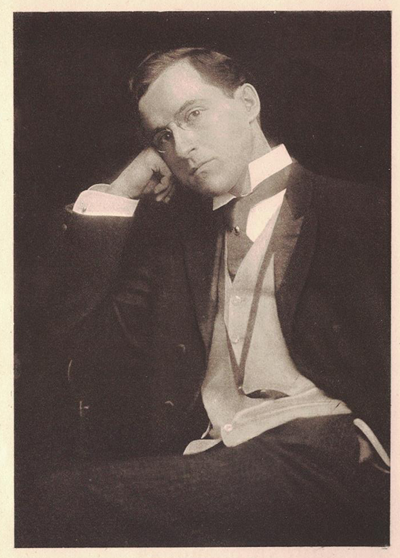

For an artist, dying young is probably the best guarantee of lasting fame. A tragic death brings public notice, weaving a mythical cloak around even a mediocre talent. And from a purely economic standpoint, when the supply is cut off, the price of a commodity inevitably rises. This is probably why we still hear faint murmurs of Arthur Upson, Minnesota’s version of John Keats or Thomas Chatterton, over a hundred years after his death in a boating accident on Lake Bemidji. Upson was thirty-one at the time of his death in 1908—a polite, bookish young man of the upper classes with five volumes of poetry and poetic drama under his belt. Two of his collections, Westwind Songs and The Tides of Spring, had garnered the poet a small national audience, his work regularly appeared in the Bellman, and Cyrus Northrop, the president of the University of Minnesota, had asked him to write some new verses for our state song, “Hail! Minnesota”.

Like the stream that bends to sea,

Like the pine that seeks the blue;

Minnesota, still for Thee:

Thy sons are strong and true!

From Thy woods and waters fair,

From Thy prairies waving far.

At Thy call they throng with a shout and song;

Hailing Thee their Northern Star!

Well, as far as state anthems go, we could have had much worse. Like his song lyrics, Upson’s refined poetry feels more at home in the 19th century than the 20th. He was born in 1877, a few years after Robert Frost, but his verse has much more in common with William Cullen Bryant: high-flown sonnets and odes that too often trip over their own grammatically contorted feet. Like Byron, he has a tendency to address poems to people he’d met or places he’d visited—but lacks Byron’s wit and personality. Upson’s simplest lyrics seem to be the most durable, channeling his gently romantic inner voice. Take “Old Gardens”, which hearkens back to the Minnesingers:

The white rose tree that spent its musk

For lovers’ sweeter praise,

The stately walks we sought at dusk,

Have missed thee many days.

Again, with once-familiar feet,

I tread the old parterre—

But ah, its bloom is now less sweet

Than when thy face was there.

I hear the birds of evening call;

I take the wild perfume;

I pluck a rose—to let it fall

And perish in the gloom.

According to Richard Burton’s (not the actor, the former head of the English Department at the University of Minnesota) introduction to his Collected Poems, Upson was born in Camden New York, and moved to Saint Paul with his family at the age of seventeen; he enrolled at the U in 1898. Upson enjoyed academia and was the editor of the Minnesota Daily, but uncertain health and financial reverses (his father appears to have been in the insurance business) forced him to drop out in his Sophomore year. Burton does not mention the exact nature of this “uncertain health,” but as Upson was well enough to work as a book agent and, one summer, as a guide at Yellowstone, my conjecture is that it was a mental breakdown. In any case, after a trip to Europe, and the publication of his first collection, At the Sign of the Harp, Upson returned to coursework at the University. Though he never completed his Senior year, he was granted a degree by the college, and even taught English there briefly. From his work it seems clear that Upson’s true aspiration was poetic immortality. It’s hard to read his sonnet “Failures” without a smidgen of irony, seeing as we are dealing with a Lost Writer:

They bear no laurels on their sunless brows,

Nor aught within their pale hands as they go;

They look as men accustomed to the slow

And level onward course ‘neath drooping boughs.

Who may these be no trumpet doth arouse,

These of the dark processionals of woe,

Unpraised, unbalmed, but whom sad Acheron’s flow

Monotonously lulls to leaden drowse?

His drama consists of The City, set in Greece during the Roman era, and The Tides of Spring. The latter, a one act drama published with a smattering of poems in 1907, is a pale Shakespearean imitation. Set in Scotland the year after the Battle of Hastings, the theme is, oddly enough, the victory of passionate youth over wise old age. As the young king, Malcolm, declares to Comnall, his elderly councilor:

This life that thrills our youth must be obeyed,

And I believe, because it comes to me

Inflowing with the holy youth of things,

That I am somehow wise in bending to it.

Taken together, Upson’s poetry and plays reveal a sensitive and intelligent young man with real talent, who preferred quiet, out-of-the-way places. As the Forward to At the Sign of the Harp declares, “It is, as it were, a Record of Echoes from many-keyed Melodies heard by a back-stairs Lodger in an old rambling Inn.” His own preference for cozy obscurity—and perhaps too, his struggles with depression—are evident in “Phantom Life”, a poem I could easily imagine as a Nick Drake song:

My days are phantom days, each one

The shadow of a hope;

My real life never was begun,

Nor any of my real deeds done.

I live so quietly I know

There must be many a sun

That does not see me as I go

Among my shadows to and fro.

Upson’s death by drowning was the subject of much speculation at the time. He had, according to some sources, attempted suicide before, and many presumed that he had intentionally jumped out of his small boat. Burton, on the other hand, seemed to believe it a tragic accident: “A few months before his passing he was affianced to one who brought him sympathy and appreciation. His health, always precarious, seemed more constant than before. There was much of encouragement, a promise of success and happiness in the outlook.”

Whatever the real story is, Upson lives on as one of the “sad young men” F. Scott Fitzgerald would later write about. Fitzgerald was eight when Upson died, and his name must have been murmured in many of the drawing rooms on Summit Avenue. It also comes up in a literary conversation in Sinclair Lewis’ Main Street. So perhaps the comment by a Mr. Aldrich, in a private letter to Burton, might in some ways have been prescient, for all its snobbery: “I am afraid he is too fine for immediate popularity; but that doesn’t matter. It is not the many but the few that give a man his place in literature. The many are engaged in canning meat and manipulating pious life insurance companies.”