| <- Back to main page |

by Cyndy Muscatel

“Now, remember. When we are in Miss Cameron’s office, you need to act very grown up. Be sure to sit up straight and fold your hands in your lap,” Mother said as we started up the steps.

“I will, Mommy,” I said. “I’m a big girl.”

We were going into Stevens Elementary School to meet with the principal. My brother was in sixth grade there, and I was supposed to be starting kindergarten. But Mother wanted me to be enrolled in first grade.

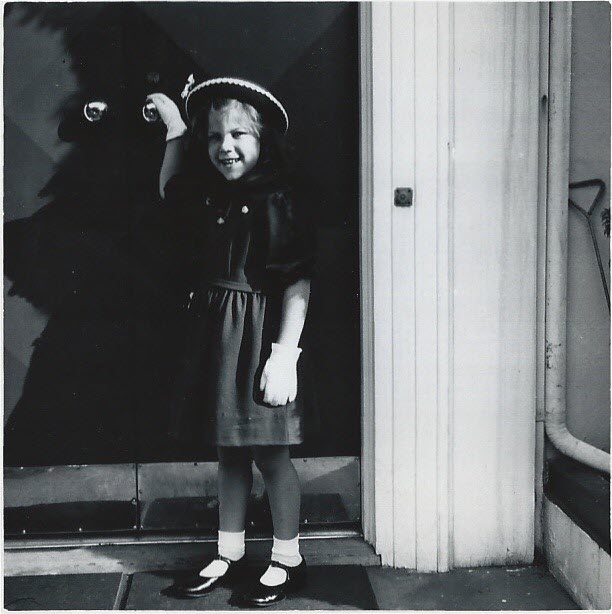

Isaac I. Stevens School was a two-story, frame building with clapboard siding. By 1950 it was showing its age. The wooden floors creaked as we walked into the principal’s office. I looked down at my Mary Janes that were making so much noise. I’d polished them with Vaseline so they were shiny as could be.

“I’m here with my daughter, Cynthia, to meet with Miss Cameron,” Mother told the secretary.

She gave us a brief nod. “I’ll tell her you’re here.”

Minutes later we were seated in Miss Cameron’s office, and Mother was explaining why she needed me to go into first grade. Miss Cameron sat at a big desk. Mother and I sat across from her. My legs stuck out straight in front of me.

“You see, Miss Cameron, my husband and I are just getting our business off the ground. We both need to be there all day. If Cynthia is in first grade, she can walk home with her brother. I don’t know what we’ll do if she has to come home at noon,” Mother said.

Miss Cameron nodded but didn’t say anything for a minute. Then she looked over at me. “Cynthia, the state of Washington says that all first graders must be six years old. You’re only five.”

I nodded, pulling my dress down so it covered my knees.

“What do you think about that?”

I didn’t know what I thought. But I knew what I needed to say.

“I know I am five, but I can act like I’m six,” I said.

Miss Cameron got up from her desk to stand right in front of me.

She tilted her head a little. “In first grade you have to wait to go to the bathroom until recess time. Do you think you can do that? That you wouldn’t have an accident?”

“I wouldn’t have an accident,” I said.

Miss Cameron smiled at my outraged tone and returned to her chair.

“You seem very grown up,” she said.

“Thank you.” I refolded my hands.

“And I can tell you have good manners,” Miss Cameron said.

She looked at Mother. “Here’s what I suggest. We’ll give Cynthia a six-month trial. If, after six months, she is doing all right, she’ll be able to stay.”

My mother gave a sigh of relief. “Thank you so much. I know she’ll do well.”

“We’ll keep an eye on her,” Miss Cameron said.

On the first day of school, I was seated toward the back of the classroom. I’d gone to preschool since I was three, but I’d never sat at a desk before. I watched one of the other kids slide into hers and followed her lead. Everyone in the room seemed to know each other, but I knew none of them. They also knew the rules and where to put things. What if I couldn’t keep up?

I knew I was on a six-month trial period, so I was on guard to do nothing wrong. But one day, when the teacher was by her desk, I asked the girl in front of me a question.

“Who is talking?” the teacher bellowed. She looked around the classroom. “Was that you, Cynthia?”

“Yes, Mrs. Attlesberger. I was asking Judith where I could sharpen my pencil,” I said.

She shook her finger at me and the class. “Talking is against the rules.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“You come up here right now,” she said.

Oh no, I thought. My six-month trial. What if the teacher says I can’t stay?

Shaking, I started toward the front of the room. The teacher grabbed me by the arm and marched me over to a stool by the blackboard.

“Sit there,” she said.

I climbed up and sat, watching her as she walked to her desk. She came back with a roll of Scotch tape. She then taped my mouth shut.

“This is what happens to little girls who talk,” she said to the class.

She made me sit there until lunchtime. Every once in a while, one of the kids would peek at me and then look away. I made sure never to make eye contact. The longer I sat there, the more desperate I felt. I knew I’d failed and Mrs. Attlesberger would report me to Miss Cameron. Mommy and Daddy counted on me and I let them down.

a

What was the result of that encounter? I stopped talking. I mean, I didn’t say much to anyone for the next five years. I went from a gregarious, laughing child to one who was withdrawn and silent. This happened seventy years ago, but I still feel a frisson of shame when I think about it.

As for the six-month trial period? Miss Cameron never told me I passed. I kept waiting but no one said anything. For a long time I thought I was still on trial—that I needed to prove myself. I waited for years to hear that I was okay. But it never came.